The unfortunate plan during early settlement by short sighted, unscientifically minded yet well meaning individuals, of releasing the pest fish gambusia (also known in America as “mosquito fish”) for Australian mosquito control, has most likely been the most damaging introduction to our native waterways.

Throughout most mainstream outlets, we occasionally hear of the destruction caused by the introduced European carp, Trout and Redfin Perch, however the damage Gambusia has bestowed upon Australia’s once pristine waterways can be directly likened to as on par (or likely even beyond) that of European carp, in terms of the total damage produced to the native ecosystem.

Even to this day, many people consider Gambusia to be “mosquito fish”, although the name is well earned in North America where the fish is native, unfortunately in Australian waters it sets our mosquito control backwards compared to if we had never introduced them in the first place.

Modern research has shown that in Australia, rather than target mosquitoes, Gambusia target other small fish which may out-compete them for the available food sources (one food source is mosquito larvae). They do this by attacking the fins of competing fish in order to immobilise them and cause death, leaving more food available for them to propagate and survive.

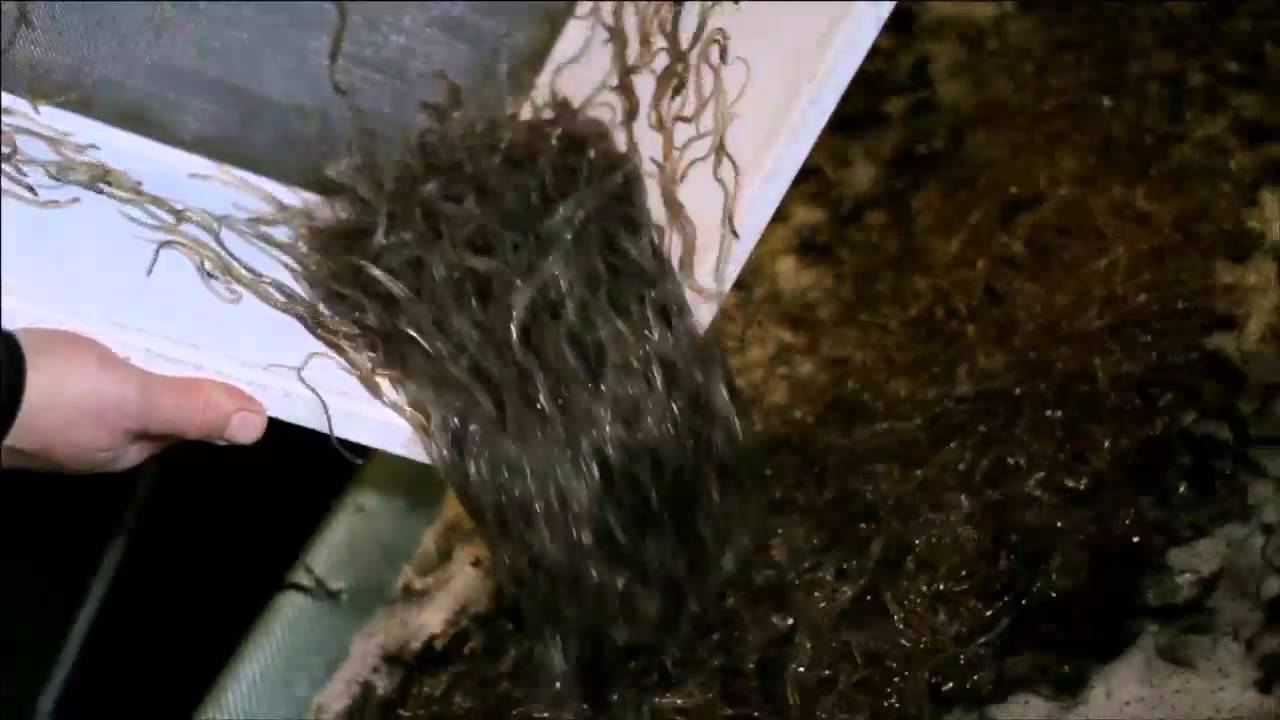

Over 100 Gambusia recovered (then dispatched) from a small bait trap left overnight in a residential creek. Location: Melbourne, Victoria. Australia.

It is not hard to see this effect if you do some basic trapping and monitoring of fish stocks, this can be done with something as simple as a cast net and a bait trap. Baiting a trap with prawn pellets or tuna based cat biscuits and leaving overnight is often the best way to attract a wide example of most small fish in the area into your traps. From my own research I can assure you, that where you find Gambusia, you will not find any small native Australian minnows, nor will you find any native freshwater shrimp.

They are driven out or killed by Gambusias aggressive survival strategies.

In their native environment in the USA, these fish do provide good benefits in relation to mosquitoes, due to the fact they have been naturalised in this environment. In Australia though, most native minnows such as Gudgeon’s, Pygmy Perch and Rainbow-fish (and numerous other lesser known species) regularly feed almost solely on mosquito larvae.

The early settlers unfortunately did not take into consideration that maybe the current native fish occupying the waters were the best option for mosquito control, the fact was they were simply feeding to capacity, they could not consume any more mosquitoes and therefore the problem could not be controlled by introduction of new species.

Unfortunately these settlers were naive, and upon simple recommendation, arranged the importation and introduction of Gambusia to back in the early 1800’s.

Their belief was the native fish were not efficient, or not plentiful enough to control the mosquitoes, in fact it was the complete opposite. The rivers were full of millions of minnows, basically to capacity, mosquitoes were simply able to breed fast enough to survive these conditions, and the problem would have been better solved with mechanical invention rather than biological control.

Introducing gambusia made the mosquito problem much worse, as the native fish consuming the majority of mosquito larva were attacked, killed and driven further downstream, the settlers learned that their introduced control fish did not prefer mosquito larvae as a preferred food source.

We now know that these fish are unable to completely sustain themselves on mosquito larvae alone, and require a wide ranging diet. The native fish on the other hand, could survive on a majority of mosquito larvae, but they were now being dispersed and their numbers dropping the further the Gambusia travelled.

The native diet of Gambusia is wide ranging, with only a small portion of their diet containing mosquito larvae. In their natural habitats food consumption is based around plankton, detritus material, many different types of insects and crustaceans. They have also been known to resort to feeding off smaller dead or dying fish, and would be viewed overall as opportunistic feeders rather than their original classification as larvivorous (eating mostly insect larvae).

To further the problem, they have a voracious appetite for shrimp, although Australia’s native fish were the best option to control mosquitoes, native shrimp such as Paratya australiensis also played a vital role in controlling mosquito larvae, and their reproduction provided a constant, easy source of food for all native fish in the waters.

Today in healthy rivers, there can be well over 100 freshwater shrimp within a 30cm square region. In regions with Gambusia however, their numbers are often observed as none. With native fish and shrimp numbers unable to recover, this removed them entirely from all habitat Gambusia controlled.

Another unfortunate victim was many native freshwater snails. Only a handful of snail species existed, although their numbers were initially highly prolific. By the late 1900’s. most native snails were driven to extinction, with the exception of one variety recently found near the Murray river, surviving by creating a refuge inside an old drainage pipe.

It is also unknown whether there were any further extinctions of species we never has the chance to study in the first place.

Native Flathead Gudgeon and Freshwater Shrimp recovered from undisclosed location in Victoria, Australia.

While it is believed only the snail species were driven entirely to extinction, we can not forget that up until the 1960’s it was not uncommon to cast a landing net into any waterway in the south eastern states and collect 30 or more pygmy perch, flathead gudgeon and native shrimp. The waterways were alive with small native fish and crustaceans for which we are now at a loss to find.

Fish such as the southern pygmy perch, although classed as not of concern population wise, are now being found in recent surveys to have as little as 20% more total population than that of the endangered Yarra pygmy perch, this has been found when testing waters where the two species are present together.

This situation would have been dismissed as nonsense of for any fisherman active in the 1960’s or earlier, as pygmy perch literally inhabited every surviving healthy waterway to near maximum capacity.

It is unfortunate that a fish such as the native pygmy perch have been driven to this level, recent surveys have shown them to be superior at mosquito control in rivers, dams and reservoirs.

The dramatic decline of Australia’s native fish is one of great sadness to the fisherman, conservationist, researcher and hobbyist, but most of all to this great land, so full of life and diversity, slowly being eroded by the mistakes of the past. One can only hope we take matters more seriously quickly, because we may not have much time left for such an opportunity.